Explained: What is Quick Commerce?

Next-day delivery used to be an innovation. Now anything more than 10 mins is "too long".

SO WHAT IS THIS MODEL IN BRIEF?

Gorillas didn’t hang around in being the fastest ever European company to reach $1 billion valuation. Getir hasn’t been slow in moving from one fundraising round to the next, with its latest Series E round valuing it at $12 billion.

The speed that the main players move befits where they compete: Quick Commerce. Which is, as the founder of Getir puts it, “1,500 everyday items delivered in an average of 10 minutes”.

It’s truly a testament to the innovation of this model that the McKinsey graphic below from a piece on the evolution of parcel delivery already needs to be adjusted and appended:

The consumer proposition might sound simple, but a completely new thinking around last mile-economics and delivery infrastructure has been required to make it a reality.

No time to waste - time to explore!

OK – SO CAN YOU TELL ME MORE?

Let’s start by differentiating between third-party delivery platforms and vertically integrated platforms

Third-party delivery platforms: deliver products from third-party retail stores such as supermarkets. In some cases, these delivery firms pick the orders while in others they only fulfil delivery

Vertically integrated models: pick from a range of essential items in their own dark stores and courier them to shoppers, typically within 10–30 minutes

Quick Commerce third-party delivery platforms can take the same delivery driver pool as a food delivery company such as Uber Eats, and apply it to pick-up from supermarkets/local stores. Hence it is no surprise Uber Eats is a lead player in this model.

Vertically integrated models are perhaps more interesting due to the fact that they create new physical and technical infrastructure tailored for delivery to consumer at speed.

So how do they work?

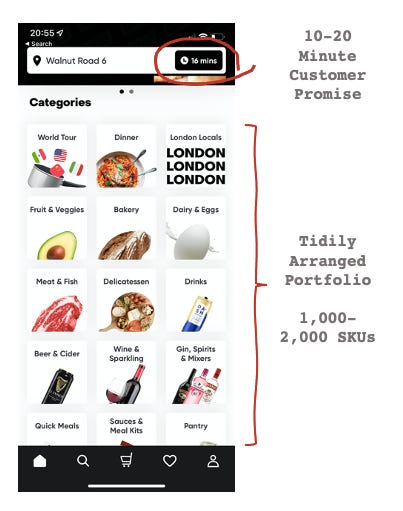

When the consumer has an urgent need for product, they order through the app. The portfolio is compressed, with a minimal number of options per product type, and between 1,000 and 2,000 items in total. The delivery promise is 10-20 minutes.

2. A key part of the infrastructure required for Quick Commerce is micro-fulfilment centres close to consumers. The Gorillas website shows all cities and areas that they serve.

We can start by looking at a smallish Dutch city where they operate: Nijmegen. I confirmed with Gorillas customer service that they have just the one fulfilment centre for this entire area.

Using census data, we can overlay population density served by one fulfilment centre: 45,000 households

If the average Dutch household spends €5,000 on groceries per year, this micro-fulfilment centre has a TAM (total addressable market) of c. €225m per year.

3. Micro-fulfilment centres have a layout which facilitates quick picking and quick dispatch. Some first observations from photos provided by Getir are stand-out features seemingly lending themselves to fast-picking.

These small incremental features add up to a super-fast pick-time

“If it’s a couple of pharmacy items, I try to do it in seven seconds. If there are 10 items, about 45 seconds”

Getir micro-fulfilment centre picker, interviewed by Sifted

Where customer promise is 10-20 minutes, being able to pick in less than a minute gifts more time to the driver that makes the final delivery

4. A blur of cyclists and motorcyclists dressed in various colours is a very visible part of modern urban life. And indeed, the smaller the vehicle, the better. Just as Picnic makes specific use of custom small vehicles to help dodge traffic, almost all Quick Commerce companies make use of two-wheeled transport.

WHY IS THIS RELEVANT TO CONSUMER GOODS?

Checking vacancy pages on Quick Commerce company websites shows departmental segmentation between Supply Chain (the “traditional” upstream supply of products) and Delivery Operations (the “innovative” downstream delivery to consumer); and this suggests the downstream operational complexity of Quick Commerce has not yet been passed on to upstream FMCG suppliers.

Future Quick Commerce company consolidation which puts more power into the hands of single players may lead to increased demand on suppliers (eg. multiple, smaller delivery drops across a micro-fulfilment centre network), but currently this is not the case.

Instead, the current demand on consumer goods companies may be in different areas:

Product margin - last-mile delivery is expensive (see below), and therefore the gross profit requirements per order to service delivery are necessarily high. Browsing the product catalog of Quick Commerce companies shows single-serve items with high price per ml much more prevalent than value-packs with low price per ml.

Customer acquisition - consumers will often search for branded manufacturer products online, but very few branded manufacturers have their own infrastructure in place to fulfil consumer demands for those products. Therefore re-directing and converting interested consumers through Quick Commerce seems to be an area of focus.

Right portfolio - if there are only 1,000-2,000 products in a portfolio, having the right products is key. That is products meeting margin expectations, as well as those attracting high sales per SKU to justify their existence within the limited online portfolio (which is deliberately narrow because those SKUs must sit in high-cost city centre micro-fulfilment centres and not massive out of town fulfilment centres similar to Amazon).

ANY SPECIFIC COMPANIES OR MARKETS OF INTEREST?

The Quick Commerce model is globally popular. It is in the Americas. It is Europe. It is in Asia. Perhaps this is unsurprising: when a consumer knows quicker delivery is possible, they want it.

And because of the fundamental premise of delivery within 15 minutes, there will be convergence of certain structural features:

There needs to be enough consumers to bring the volume that makes the model economics work = being in densely populated metropolitan areas

The consumer needs to be serviced quickly = having fulfilment centres close to the consumer and delivery with transport modes that can weave through traffic

Space in urban areas is expensive = micro-fulfilment centres with small portfolio selection

These common structural features would seem to lend themselves to a scaleable business model, and indeed Getir has scaled from one city in one country (Istanbul, Turkey) to nine countries.

However, the scaleable elements are more related to the expertise in setting up radically new operating models. There is not an inherent network effect: an existing Getir user does not get any incremental benefit from each new user that joins the Getir platform.

Retailers historically have not expanded much internationally (in comparison to FMCG brands) due to thin retail margins which could not support building dozens of stores and a lack of truly unique retail concepts1. Well-funded Quick Commerce companies do by contrast have somewhat higher retail margins and unique retail concepts.

On a line between a completely borderless business model like Instagram and a necessarily local model like Carrefour, Quick Commerce companies sit somewhere in between.

WHAT ARE THE ECONOMICS OF THE BUSINESS MODEL?

In a report on Quick Commerce, Dutch broadcaster NPO broke-down the cost of the model, translated and duplicated below (figures in euros):

It seems that the retailer gross margin is high at around 30%. A brick and mortar retailer in contrast would be more like 10%.

However, there are two main costs which Quick Commerce has to contend with that offline commerce does not.

Last Mile Delivery

The most costly part of getting a product to the consumer is last mile delivery, because at this point mass principles of manufacturing and shipping are squashed under unique consumer delivery requests.

In a previous article, I discussed how the Milkman 2.0 model pioneered in Netherlands by Picnic would build a wait list of customers and only release access to the service when a certain delivery density existed along a fixed route, thereby ensuring sufficient volume aggregation and an optimal number of drops per hour to offset last mile delivery costs.

However, the Quick Commerce model does not have such luxuries. Because of its consumer promise of “faster than you” (Gorillas), “ice cream in minutes” (Getir) etc., there is a limited time window within which to get more orders to aggregate volume without breaching the consumer promise.

This cost challenge can be offset by reducing labour (eg. through using drones or autonomous vehicles to deliver) or by passing it through to the consumer, although based on the above figures this it not currently done.

2. Promotions (Discount Codes + Advertising)

It seems truly remarkable that the current amount spent on discount codes and advertising is at parity to the amount the consumer pays for their order, but this is likely a symptom of companies awash with venture capital seeking to gain market advantage.

We are already starting to see consolidation amongst Quick Commerce companies as this is needed to achieve efficient utilization of dark stores and delivery fleets.

“A company will be able to enjoy efficiencies only when it has almost full control over a catchment area and its dark stores have 80-100% utilization”

As a dominant player emerges in markets, there will be more levers which can be pulled on the path to profitability such as higher order density and batching, lower promotional requirements, and customers paying a higher amount for convenience.

ANYTHING ELSE OF INTEREST?

With grocery fulfillment under the Quick Commerce model already down to 10 minutes, it is not clear what can be done to bring this down further. Micro-micro-fulfilment centres (AKA vending machines) with c. 100 critical SKUs across neighbourhoods?

Thain, G. and Bradley, J., 2012. Store wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.