Explained: What are Virtual Restaurant Brands?

No shopfront. No real restaurant. No physical consumer access. Just a brand on the app

SO WHAT IS THIS MODEL IN BRIEF?

More details later. First: the genesis.

In the bible, god layers each day’s creations on top of the previous. Each stage follows on logically and sequentially. So it is with the business models to get virtual restaurant brands.

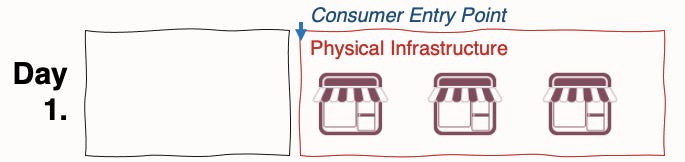

In the beginning there were restaurants. The first establishments recognisable as restaurants emerged in 12th century China to serve travelling tradesmen in Hangzhou and Kaifeng.1

Then come delivery services. By foot at first (Asia again - cold noodles delivered in 17682), then with bicycles and scooters.

Slowly, tech allows aggregation of the delivery service network. GrubHub started as an app offering a simple, quick look-up site for restaurants with delivery service in the neighbourhood.3

As the platform is build out and consumers rely on it as a source of information, so it is possible to bundle in payment services and obtain a cut of transaction revenue.

“The places the consumers love can’t deliver and we also found out about delivery drivers that had a ton of spare time and… wanted to earn extra cash”

Tony Xu, DoorDash

This was the inception for creating a fleet of tech-platform affiliated delivery drivers.

By now the restaurant indexation platform, the payment platform, and the delivery network is owned by the tech provider. And so is the consumer embedded within the ecosystem. More disconnected than ever from the restaurant that actually cooks their food, so the stage is set for the creation of virtual restaurant brands living inside of real restaurants

OK – SO CAN YOU TELL ME MORE?

Let’s start with an explanation of a relevant parallel business model: ghost kitchens.

My first introduction to Ghost Kitchens was in China. I stumbled across a group of delivery drivers lounging around on their scooters, some smoking, some mindlessly fondling their phone, some catching a nap under the sweltering summer sun. One by one, their phones would ping and they would go through a door, only to seconds later come back out with an order. They would pack the order into their delivery bag and start their ignition in the direction of wherever the customer demand had sent them.

I knew the brand in their plastic bags - it was one of my favourite tea brands. But there was no visible storefront there. So what was going on?

Once delivery demand and off-premises consumption exceeds pick-up demand and on premises consumption→ kitchens should be optimised for delivery

Staff structure with balance between service and preparation → tilted towards preparation

Premises footprint orientated towards customer accessibility → tilted towards delivery driver accessibility, with customer spaces no longer needed

Let that sink in for a second: customer spaces no longer needed. These kitchens would have to be relatively well located to reach the end customer, but all of the niceties of front-of-house operations could be removed. Even windows to the world outside. Hence, ghost kitchens or dark kitchens.

By this stage the consumer starts to become disconnected from the actual place that cooks their food or prepares their drink. The consumer shopfront is no longer the faded canopy of the local Italian, but the restaurant listing in the app. The food ordered is no longer the tasty looking food pointed to on someone else’s table, but the pixels on the screen.

And the switch and bait can begin. If the consumer shopfront is not needed, it can exist virtually within a ghost kitchen. Or it can exist within another restaurant.

Put another way, the pasta the consumer clicks-on on the screen can be prepared in a dedicated ghost kitchen. Or it can be prepared in the local Indian restaurant. The fact is it can be prepared anywhere. The food only exists in a conceptual form in the app. Hence the creation of app-based food brands which have no physical location and have never had any physical location.

And of course, pick-up is not possible. Because the whole conceit would instantly come tumbling down as soon as the consumer arrives at their local Indian to pick up their pasta.

WHY IS THIS RELEVANT TO CONSUMER GOODS?

Let us take some consumer purchase decision trees as a mental model to understand the impact of virtual restaurant brands on consumer goods and retail companies. At first appearances, the downside seems limited - consumer goods companies (at least those focusing on food etc.) belong to the scratch cooking branch of make. Likewise, retailers operate primarily across the make branch.

Therefore, the disruption is going to happen more to the extant economic flows within the buy branch (dine-in, take-out and delivery).

In fact, unlike most new business models which seem to signal doom and fear for the manufacturers of branded goods, this is a model which should get a brand managers juices flowing. Direct to Consumer models would seem to offer FMCG companies the halcyon of channel ownership, but in reality the products of many consumer companies are not so profound as to justify consumers using it in a dedicate way.

Even digitally native companies with exceptional loyalty (such as millennial’s favourite shoe company Allbirds) struggle to make the model work. Recent Direct to Consumer IPO filings for the company indicate it is has never yet reached profitability. The strong consumer awareness and distribution of incumbent brands is just too powerful.

Yet, with virtual restaurant brands, a brand can piggyback on an existing infrastructure. This offers new revenue streams and channels without insisting on dedicated consumer channels. As discussed above, the evolution of restaurant apps and the way the consumer interacts with them has created a consumer that does not overthink the physical location from which their product is sourced. The brand and proposition overrides dispatch origin in significance.

So all of a sudden, the right brand can become a store in itself by leveraging the restaurant networks around cities which in essence act like hyper-micro fulfilment centres (let’s assume fulfilment centres might be on a per city basis, micro-fulfilment centres would have for example several per city for rapid grocery, whereas restaurants already connected to the delivery network are even more numerous.)

Just like that, Häagen-Dazs or Ben & Jerry's could put a tub of their ice-cream into freezer cabinets across a city. They could set up a virtual store on a delivery app, which also takes care of fulfilment. A virtual restaurant brand proposition is created with no physical infrastructure required.

ANY SPECIFIC COMPANIES OR MARKETS OF INTEREST?

There are two pools of companies we should be interested in.

The first pool of companies are those which facilitate the establishment of virtual restaurant brands.

In “The Virtual Future of Restaurants” podcast4, Land of the Giants took a look at Alex Canter, who in 2017 was part of a company called Ordermark. They were set up to help streamline how restaurants manage orders coming in from the multiple delivery apps by creating an app that integrated all platforms onto one. This app opened up a world of possibilities: it them became possible to see consumer purchasing behaviour and what menu items were trending.

This let Canter to a company called Nextbite, founded in 2019, which brings us closer to the world of virtual restaurant brands. This company is all about inventing delivery-only digital restaurants. Here’s how it works: through OrderMark, Nextbite has access to key data about consumer transactions and behaviour and it applies to that data to some key questions:

what is going to be hot next year?

how do we take concepts that are doing well in certain areas and bring them to new areas to spread food in new ways which has never been done before?

And from here, we are led to a second pool of relevant companies - the virtual brands themselves.

To take an example, one trend which Nextbite noticed was that hot chicken sandwiches were becoming popular in cities like LA and NY. Nashville is the home of this food, and there were so many markets which had no access to these foods. So in 2019 they created the virtual brand called Miss Mazy’s Amazin’ Chicken.

To detail the process for onboarding:

Restaurants would sign up and then use their existing restaurants to make the food. They get the approved list of ingredients, the recipes, the packaging, everything needed to make and sell the concept. And they profit from the growing consumer desire for hot chicken sandwiches

“The Virtual Future of Restaurants” on Land of the Giants Podcast

From here, virtual restaurant brands spiralled even further as a concept. Even celebrities became involved. Wiz Khalifa set up a virtual brand called HotBox by Wiz.

HotBox by Wizz caters to a market which Nextbite noticed was untapped: late night diners. So NextBite pinpointed the opportunity and then Wiz Khalifa helped create the menu, the branding, and the advertising campaign. He can have a restaurant brand without actually having physical restaurant infrastructure.

He is not hiring a staff or finding a venue or anything. He is simply creating an identify.

WHAT ARE THE ECONOMICS OF THE BUSINESS MODEL?

When the virtual restaurant brand food sells, everyone gets a cut. But let’s compare the revenue and cost tranches to the standard app-based delivery model.

The virtual restaurant brand MC (NextBite in the example above)

This is an additional layer of cost created, but the value brought is providing commercial kitchen operators with fully branded restaurant concepts in areas where latent demand is already identified

The brand (Wiz Khalifa)

The association with a brand may justify higher sales price due to the fact that established brands now setting up a (virtual) restaurant infrastructure possess “mind space” and trust with consumers

The delivery operators (eg. Deliveroo)

The only uptick in revenue for delivery operators would be if the presence of virtual restaurant brands creates a consumer shift from another one of the “hungry” branches in the example above to delivery

The local restaurants

The service workers producing the products are likely not being paid more, but the layering of additional restaurant brands and propositions (particularly where the brands entail cooked goods) requires more work, skill; and therefore potentially staff pay and turnover.

Of course, the hope of all those kitchen operators who take a restaurant brand into their establishment is the hope that they can get more revenue allocated over an existing staff and resource cost base. This would lead to greater profitability.

And this does seem to be the case. There are examples of existing restaurants segmenting one extended menu into four distinct and focused menus, each with its own brand and orientated around a very specific and targeted proposition which the consumer would then search for in the app. The sum of the four new menus would be almost four times that of the original extended menu, even though the food is being produced in the same kitchens, with the same ingredients, and the same staff5. This is invariably a business model other restaurants would like to repeat.

ANYTHING ELSE OF INTEREST?

Day 7 probably won’t be bringing any rest. The innovation machine continues faster than ever, creating ever more scary and ever more exciting worlds for food eaters, food makes, and food intermediaries.

Rawson, Katie. Dining Out: A Global History of Restaurants (Reaktion Books, 2019)

http://www.seouland.com/arti/culture/culture_general/354.html

https://www.businessinsider.com/grubhubs-ceo-on-the-shock-of-outgrowing-three-offices-in-a-few-short-years-2012-2?international=true&r=US&IR=T

“The Virtual Future of Restaurants” on Land of the Giants Podcast

After Hours Podcast