Analysed: The Economics of Panic Buying

How keeping the shelves stocked seems to be the most challenging new business model of all

“Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose”. The more things change the more they stay the same.

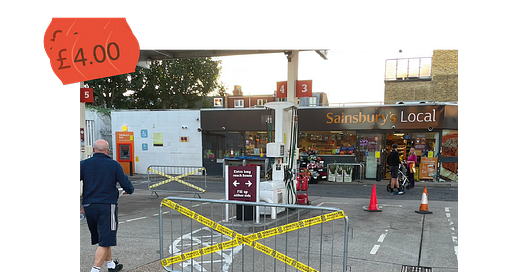

Last year, for the first time in my life, I witnessed panic buying of toilet paper. Flash forward to autumn 2021: UK is now out of Covid and people are heading out of their houses. Yet once again, panic buying rears its head with shortages at the British petrol (American English: gas) pumps.

I am a retail and consumer good aficionado. My ear is tuned to the newest of industry business models. But of all topics in the industry, panic buying receives the most mass-media attention.

Yet panic buying is not based on actual upstream supply issues. It is a psychological condition, accentuated by media frenzy to the point it can then physically present itself at point of sale on supermarket shelves or at petrol pumps.

It would of course be best that no-one panic buys. But if you are worried that supplies might run out because other people will beat you to purchase, then it makes sense for you to rush out to buy as well.

That the consumer would suffer from panic buying makes sense. But the product suppliers suffer as well. During last year’s toilet paper crisis I deconstructed the economics of panic buying from the position of the consumer goods manufacturer. Let me cover that again now, before drawing a short contrast with the current panic buying crisis.

During the early stages of the Covid period, toilet paper companies were business broadsheet darlings, Kimberly-Clark being one such example.

Taking the end of February when lockdowns began as the benchmark, side-by-side comparison of the indices of Kimberly-Clark (KMB) vs. S&P Global 100 (measuring the performance of 100 top multi-national companies) does suggest that yes, these shares over-performed versus the market.

But for me at the time, I was baffled by this. I felt that the disruption to business model would surely be more harmful than beneficial…

The following was written in April 2020

If profit is the overarching goal of a mature company, let’s break down to first principles of the P&L and take these levers one by one.

Revenue = Volume x Price

Profit = Revenue - Costs

Volume

Expected Long Term Demand-Side Volume Change = None.

It is certainly true that there is a short term spike in terms of demand for toilet paper. This is clearly evident by empty super market shelves.

However, what if we think about this from the perspective of longer term consumer habits. Are consumers suddenly going to the toilet more? Probably not. Are they going to be going to the toilet more over the next year? Probably not.

The frequency of consumption is not significantly increasing. The frequency of consumption may even decrease, since consumers will have anchored in their minds: “there is a shortage of toilet paper, I better use less”.

Therefore, what we can say is that the total latent demand for toilet paper is not increasing.

Expected Long Term Supply-Side Volume Growth = Down.

Although point of sale availability will recover over the long term, as things stand supermarket shelves are out of stock. In simple terms, this means that demand is not being met by supply. If we follow through on the assumption that total long-term demand is not up, inability to meet that demand at any stage is almost certainly going to lead to loss of turnover.

The benefits of the shortages are more likely to be felt by the smaller brands in the market who conventionally suffer from lower brand awareness. When there are product shortages, consumers show themselves to be severely disloyal and prepared to compromise to get hold of anything.

Price

Expected Long Term Price Growth = Up.

One benefit which will come out of increased short-term demand is that toilet paper companies will not be forced into price promotions to drive sales. I suspect that promotions would probably not be significantly used for driving volume in a stable and non-innovative category such as toilet paper anyway, with the emphasis likely on creating additional multipack sizes which incentivise consumers to buy more. Therefore, though there may be a slight price growth yield in the short-term, I do not envisage this would significantly compensate for the long term inability to meet demand.

Costs

Expected Long Term Costs = Up.

Reacting to meet demand spikes is going to be costly. These costs are going to sit at each node of the supply chain: increased supplier payments to guarantee input materials, increased overtime pay to keep the machines on in the factory, increased speedy dispatch shipments to meet out of stocks. All of these things might seem insignificant to the toilet paper company at the time as they try to meet the crazy demand. But when they look pack at their cost metrics for the year (such as cost per ton sold), I have no doubt that these will be higher than 2019.

To conclude, I do not view the current Covid demand spike for toilet paper as being beneficial. With long run volume down, long run price only slightly up, and costs up; the P&L at the end of the year is almost certainly going to look much less rosy than it did in 2019

The markets ended up proving my hypothesis correct. Despite the initial over performance of shares of large toilet paper companies, they have trailed off significantly in the one year since, a reflection of poor performance and commodity inflation.

Yet at that point in 2020, when consumers had no idea how long Covid would go on, whether they would even be able to get out of their houses, their actions made sense. It just didn’t really help the companies selling them the products that much.

Flash forward to the petrol panic buying crisis of 2021, and one significant difference to what we saw previously is that for petrol, it is an enabler for driving; which is a loosely-substitutable habit.

This means that there are alternative options for the user. They could use mass rapid transit options such as buses or trains. They could use personal transport such as cycling. Of course, none of this is particularly good for the companies selling petrol.

But my dad believes that this is not a bad thing, that it is pushing us towards making positive changes in our behaviours. Just in the same way that the Covid period forced many of us to reflect on how happy we were in our jobs and with our lives, so too does an energy crisis give us the chance to reflect on how we could be more green.

Though the challenges we face may change, each challenge gives us an equal opportunity to reflect on its impact on us as individuals and how we can grow and evolve.